Plato is a programming language that I decided to create as a personal challenge and also as a hobby. I have always been fascinated with programming languages, ever since I started university and used an educational IDE called Calango. It was meant to help you learn how to code and have better logical thinking. It also had its own programming language, which I assume is also called Calango, and was a lot easier than the c language we were first using. Later I found out that students had made this IDE as a capstone project, so I thought to myself: “If they could do it, so could I”. Well, the thing is, creating a new programming language is not as simple as sitting down in front of your favorite IDE and starting typing like a brainless monkey. No offense intended to monkey readers.

So here are the main characteristics my programming language is going to have:

- It’s going to be called Plato, in homage to the ancient Greek philosopher.

- It’s going to be an interpreter language.

- It is a high-level, imperative, structured programming and gradually typed language.

- It’s going to be built using Swift because I will be able to make apps with it.

- I want the syntax to be modern and easy to learn.

- It’s intended for people who are learning how to code.

So yeah, that’s it for the moment. I am not aiming for it to be the next amazing programming language, but rather to learn the process of making one. I’m going to use this post to document what I have learned and how I achieved my goals.

Index

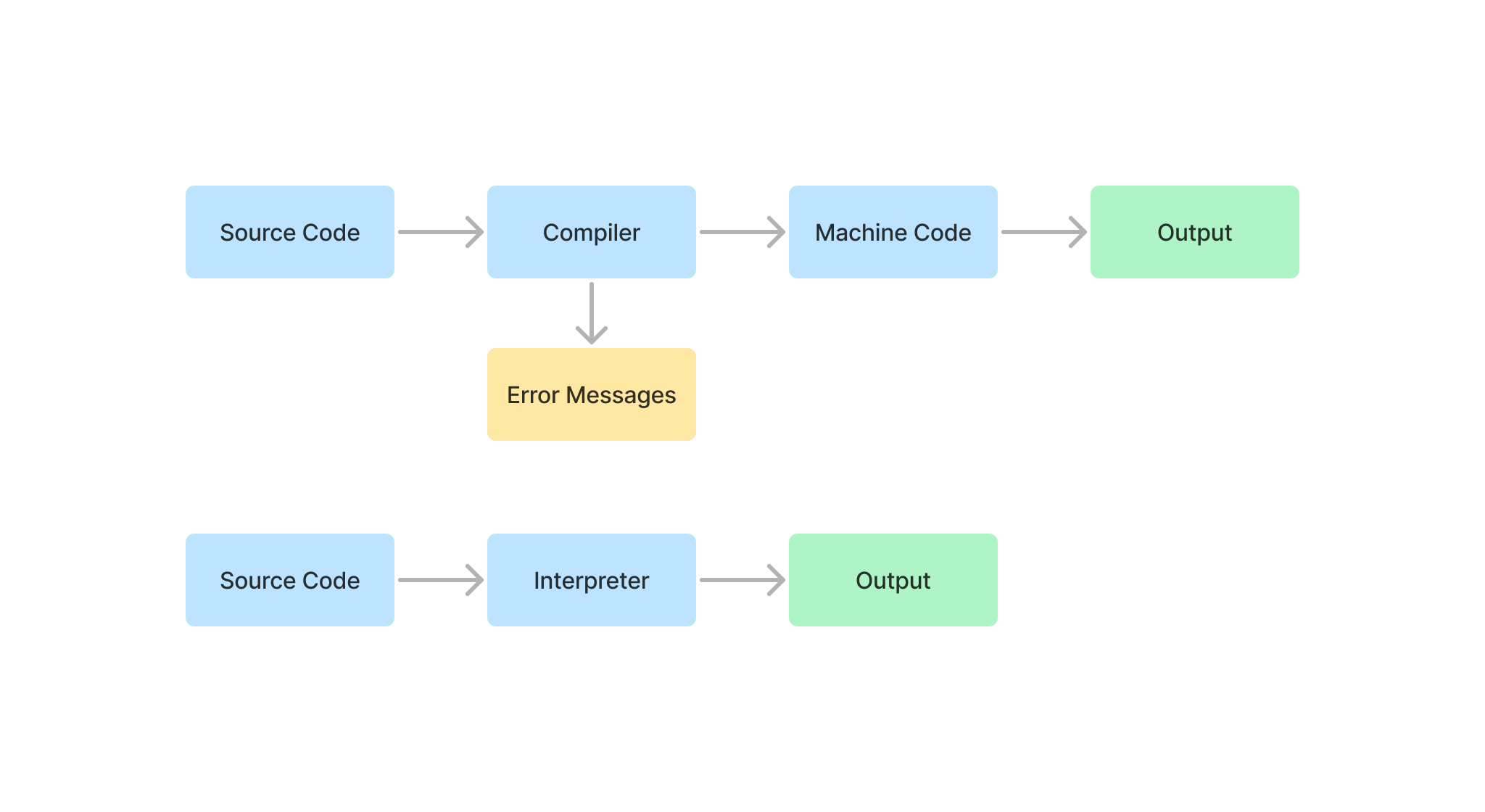

1. Interpreter vs compiler

A compiler is responsible for delegating the semantics of your language to a target language. What that means is that it is not responsible for actually running the code but rather “translating” it to another language, like machine code. Well then, how does that machine code run? It has an interpreter of its own, which is responsible for implementing the executing the commands. In the case of such low-level machine codes, the CPU is the interpreter itself. Popular interpreters that we have are Python, Ruby, and JavaScript. Each one of them executes the code line by line.

| Interpreter | Compiler |

|---|---|

| Implement semantics themselves | Delegate semantics to a target language |

| No Intermediate Object Code is Generated | Intermediate Object Code is Generated |

| Compilation and execution take place simultaneously | The compilation is done before execution |

| Slower (But there are optimization techniques) | Comparatively faster |

| Displays error of each line one by one | Display all errors after compilation, all at the same time |

| AST-based (recursive) interpreters | Ahead-of-time (AOT) compilers |

| Bytecode-interpreters (VM) | Just-in-time (JIT) compilers |

| AST-transformers (transpilers) | |

| Examples: Python, Pearl, PHP, Ruby, etc. | Examples: C, C++, C#, Scala, Java, etc. |

Compiler vs Interpreter

1.1 What is object code?

In computing, object code or object module is the product of a compiler.

In a general sense object code is a sequence of statements or instructions in a computer language, usually a machine code language (i.e., binary) or an intermediate language such as register transfer language (RTL). The term indicates that the code is the goal or result of the compiling process, with some early sources referring to source code as a “subject program”.

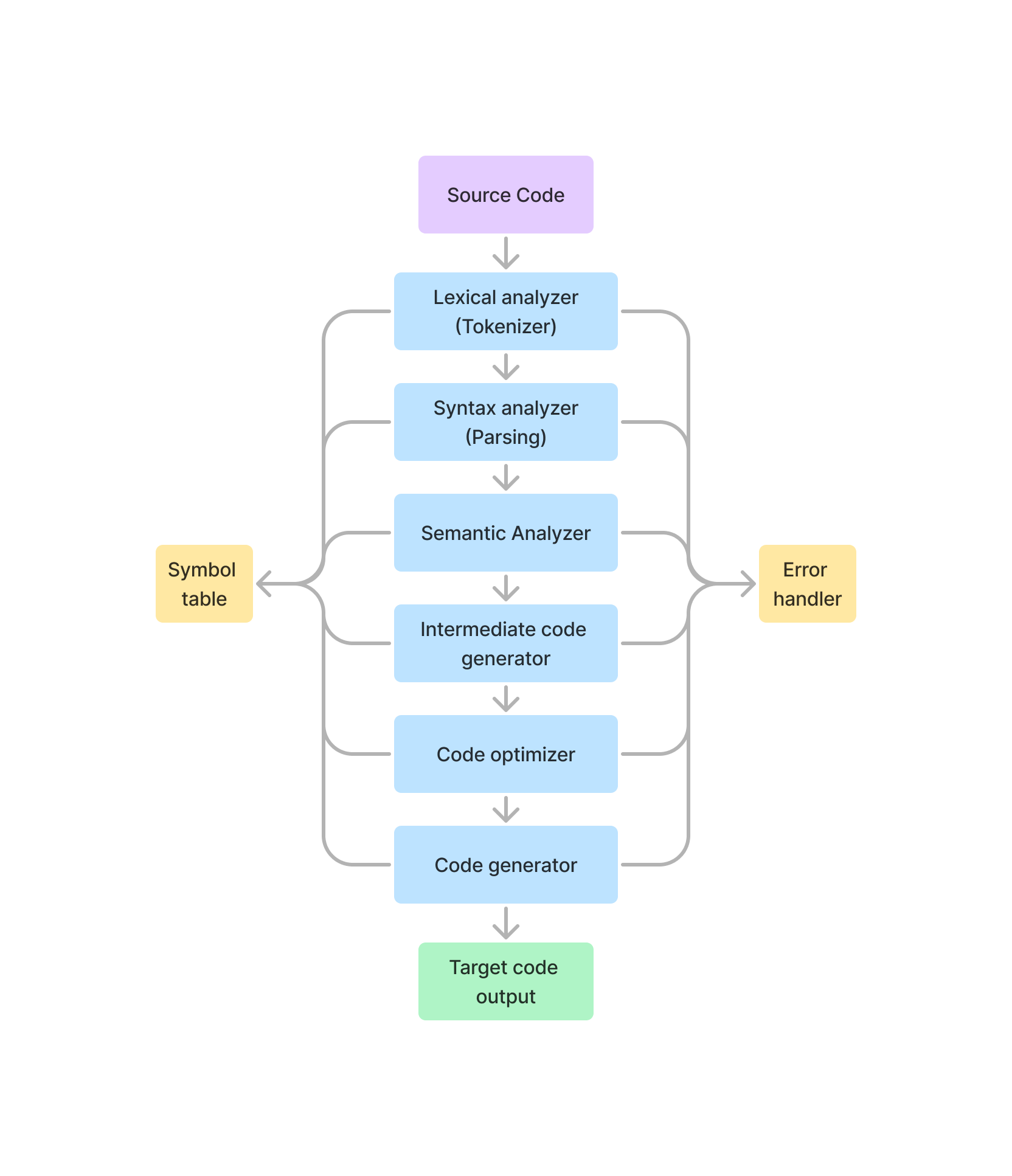

1.2 Phases of a compiler

- Lexical Analyzer (Tokenizer): It scans the code as a stream of characters, groups the sequence of characters into lexemes, and outputs a sequence of tokens with reference to the programming language.

- Syntax Analyzer (Parsing): In this phase, the tokens that are generated in the previous stage are checked against the grammar of the programming language, whether the expressions are syntactically correct or not. It makes parse trees for doing so.

- Semantic Analyzer: It verifies whether the expressions and statements generated in the previous phase follow the rule of programming language or not and it creates annotated parse trees.

- Intermediate code generator: It generates an equivalent intermediate code of the source code. There are many representations of intermediate code, but TAC (Three Address Code) is used most widely.

- Code Optimizer: It improves the time and space requirement of the program. For doing so, it eliminates the redundant code present in the program.

- Code generator: This is the final phase of the compiler in which the target code for a particular machine is generated. It performs operations like memory management, Register assignment, and machine-specific optimization.

The interpreter performs lexing, parsing, and type checking similar to a compiler. However, the interpreter processes the syntax tree directly to access expressions and execute statements rather than generating code from the syntax tree.

1.3 Statically Typed vs Dynamically Typed Languages

| Statically Typed | Dynamically Typed |

|---|---|

| Type checking is completed at compile time | Type checking is completed during runtime |

| Explicit type declarations are usually required | Explicit declarations are not required |

| Errors are detected earlier | Type errors are detected later during execution |

| Variable assignments are static and cannot be changed | Variable assignments are dynamic and can be altered |

| Produces more optimized code | Produces less optimized code, runtime erros are possible |

1.4 What are Parsers?

Parsing, syntax analysis, or syntactic analysis is the process of analyzing a string of symbols, either in natural language, computer languages or data structures, conforming to the rules of a formal grammar.

A. In computer languages

A parser is a software component that takes input data (frequently text) and builds a data structure. Often some kind of parse tree, abstract syntax tree or other hierarchical structure, giving a structural representation of the input while checking for correct syntax.

The parser is often preceded by a separate lexical analyzer, which creates tokens from the sequence of input characters.

Parsers may be programmed by hand or may be automatically or semi-automatically generated by a parser generator.

B. Overview of process

The following example demonstrates the common case of parsing a computer language with two levels of grammar: lexical and syntactic.

The first stage is the token generation, or lexical analysis, by which the input character stream is split into meaningful symbols defined by a grammar of regular expressions. For example, a calculator program would look at an input such as “12 * (3 + 4)^2” and split it into the tokens 12, *, (, 3, +, 4, ), ^, 2, each of which is a meaningful symbol in the context of an arithmetic expression. The lexer would contain rules to tell it that the characters *, +, ^, ( and ) mark the start of a new token, so meaningless tokens like “12*” or “(3” will not be generated.

The next stage is parsing or syntactic analysis, which is checking that the tokens form an allowable expression. This is usually done with reference to a context-free grammar which recursively defines components that can make up an expression and the order in which they must appear. However, not all rules defining programming languages can be expressed by context-free grammars alone, for example type validity and proper declaration of identifiers. These rules can be formally expressed with attribute grammars.

The final phase is semantic parsing or analysis, which is working out the implications of the expression just validated and taking the appropriate action. In the case of a calculator or interpreter, the action is to evaluate the expression or program; a compiler, on the other hand, would generate some kind of code. Attribute grammars can also be used to define these actions.

C. Types of parsers

Top-down parsing Is a parsing strategy where one first looks at the highest level of the parse tree and works down the parse tree by using the rewriting rules of a formal grammar. LL parsers are a type of parser that uses a top-down parsing strategy.

note: Top-down parsers cannot handle left recursion

E : E + T

: T

;

T : T * F

| F

;

F : number

;

func E() {

// This will cause an infite loop

return E() && term("+") && T();

}

Bottom-up parsing Recognizes the text’s lowest-level small details first, before its mid-level structures, and leaving the highest-level overall structure to last.

D. LL Parser

An LL parser (Left-to-right, leftmost derivation) is a top-down parser for a restricted context-free language. It parses the input from Left to right, performing Leftmost derivation of the sentence.

E. LR Parser

LR parsers are a type of bottom-up parser that analyze deterministic context-free languages in linear time. LR parsers can be generated by a parser generator from a formal grammar defining the syntax of the language to be parsed. They are widely used for the processing of computer languages.

An LR parser (left-to-right, rightmost derivation in reverse) reads input text from left to right without backing up (this is true for most parsers), and produces a rightmost derivation in reverse: it does a bottom-up parse.

2. Formal Grammar

Formal grammar describes how to form strings from an alphabet of a formal language that is valid according to the language’s syntax. A grammar does not describe the meaning of the strings or what can be done with them in whatever context—only their form. A formal grammar is defined as a set of production rules for such strings in a formal language.

Example 1

Suppose we have the following production rules:

- $S\rightarrow aSb$

- $ S\rightarrow ba $

Then we start with S and can choose a rule to apply to it. If we choose rule 1, we obtain the string aSb. If we then choose rule 1 again, we replace S with aSb and obtain the string aaSbb. If we now choose rule 2, we replace S with ba and obtain the string aababb, and are done. We can write this series of choices more briefly, using symbols: $S \Rightarrow aSb \Rightarrow aaSbb \Rightarrow aabaab$

This grammar is context-free (only single nonterminals appear as left-hand sides) and unambiguous.

Example 2

Suppose the rules are these instead:

- $S \rightarrow a$

- $S \rightarrow SS$

- $aSa \rightarrow b$

This grammar is not context-free due to rule 3 and it is ambiguous due to the multiple ways in which rule 2 can be used to generate sequences of Ss.

That same language can alternatively be generated by a context-free, nonambiguous grammar; for instance, regular grammar with rules.

- $S \rightarrow aS$

- $S \rightarrow bS$

- $S \rightarrow a$

- $S \rightarrow b$

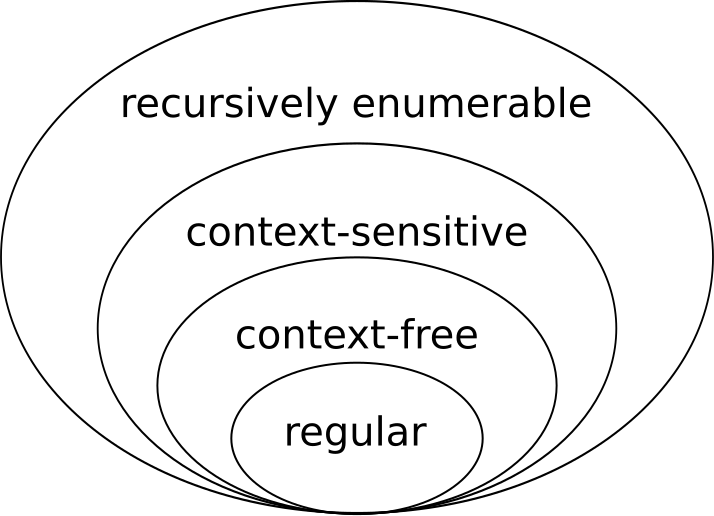

2.1 Chomsky hierarchy

The Chomsky hierarchy is a containment hierarchy of classes of formal grammars. Each class can also completely generate the language of all inferior classes.

| Grammar | Languages | Recognizing Automaton | Production rules | | — | — | — | — | | Type-3 | Regular | Finite state automaton | $A \rightarrow a$ and $A \rightarrow aB$ | | Type-2 | Context-free | Non-deterministic pushown automaton | $S \rightarrow \alpha $ | | Type-1 | Context-sensitive | Linear-bounded non-deterministic Turing machine | $\alpha A \beta \rightarrow \alpha \gamma \beta $ | | Type-0 | Recursively enumerable | Turing machine | $\gamma \rightarrow \alpha $($\gamma$ non-empty) |

A. Context-free grammar

A context-free grammar is a set of recursive rules used to generate patterns of strings. A context-free grammar can describe all regular languages and more, but they cannot describe all possible languages.

Context-free grammar are studied in the fields of theoretical computer science, compiler design, and linguistics. CFGs are used to describe programming languages and parser programs in compilers can be generated automatically from context-free grammars.

Context-free grammars have the following components:

- A set of terminal symbols which are the characters that appear in the language/strings generated by the grammar. Terminal symbols never appear on the left-hand side of the production rule and are always on the right-hand side.

- A set of nonterminal symbols (or variables) that are placeholders for patterns of terminal symbols that can be generated by the nonterminal symbols. These are the symbols that will always appear on the left-hand side of the production rules, though they can be included on the right-hand side. The strings that a CFG produces will contain only symbols from the set of nonterminal symbols.

- A set of production rules which are the rules for replacing nonterminal symbols. Production rules have the following form: variable $\rightarrow$ string of variables and terminals.

- A start symbol is a special nonterminal symbol that appears in the initial string generated by the grammar.

Formal Definition

A context-free grammar can be described by a four-element tuple ($V , T , P , S$), where

- $V$ is a finite set of variables (which are non-terminal);

- $T$ is a finite set of terminal symbols;

- $P$ is a set of production rules where each production rule maps a variable to a string;

- $S$ which is a start symbol;

2.2 Parsing expression grammar

In computer science, a parsing expression grammar (PEG) is a type of analytic formal grammar, i.e. it describes a formal language in terms of a set of rules for recognizing strings in the language. The formalism was introduced by Bryan Ford in 2004[1] and is closely related to the family of top-down parsing languages introduced in the early 1970s. Syntactically, PEGs also look similar to context-free grammars (CFGs), but they have a different interpretation: the choice operator selects the first match in PEG, while it is ambiguous in CFG. This is closer to how string recognition tends to be done in practice, e.g. by a recursive descent parser.

Examples

Expr ← Sum

Sum ← Product (('+' / '-') Product)*

Product ← Power (('*' / '/') Power)*

Power ← Value ('^' Power)?

Value ← [0-9]+ / '(' Expr ')'

2.3 Backus–Naur form

In computer science, Backus–Naur form or Backus normal form (BNF) is a metasyntax notation for context-free grammars, often used to describe the syntax of languages used in computing, such as computer programming languages, document formats, instruction sets and communication protocols. It is applied wherever exact descriptions of languages are needed: for instance, in official language specifications, in manuals, and in textbooks on programming language theory.

How to write:

- symbol is a nonterminal variable that is always enclosed between the pair <>.

::=means that the symbol on the left must be replaced with the expression on the right.-

expression consists of one or more sequences of either terminal or nonterminal symbols where each sequence is separated by a vertical bar **” “** indicating a choice, the whole being a possible substitution for the symbol on the left.

<symbol> ::= __expression__

Example

As an example, consider this possible BNF for a U.S. postal address:

<postal-address> ::= <name-part> <street-address> <zip-part>

<name-part> ::= <personal-part> <last-name> <opt-suffix-part> <EOL> | <personal-part> <name-part>

<personal-part> ::= <first-name> | <initial> "."

<street-address> ::= <house-num> <street-name> <opt-apt-num> <EOL>

<zip-part> ::= <town-name> "," <state-code> <ZIP-code> <EOL>

<opt-suffix-part> ::= "Sr." | "Jr." | <roman-numeral> | ""

<opt-apt-num> ::= "Apt" <apt-num> | ""

Variants

- EBNF

- ABNF

2.4 What is syntactic ambiguity?

Syntactic ambiguity, also called structural ambiguity, amphiboly or amphibology, is a situation where a sentence may be interpreted in more than one way due to ambiguous sentence structure.

Syntactic ambiguity does not come from the range of meanings of single words, but from the relationship between the words and clauses of a sentence, and the sentence structure hidden behind the word order. In other words, a sentence is syntactically ambiguous when a reader or listener can reasonably interpret one sentence as having multiple possible structures.

2.5 What is an abstract syntax tree?

An abstract syntax tree (AST) is a data structure used in computer science to represent the structure of a program or code snippet. It is a tree representation of the abstract syntactic structure of text (often source code) written in a formal language. Each node of the tree denotes a construct occurring in the text. It is sometimes called just a syntax tree.

A. Application In compilers

Abstract syntax trees are data structures widely used in compilers to represent the structure of program code. An AST is usually the result of the syntax analysis phase of a compiler. It often serves as an intermediate representation of the program through several stages that the compiler requires, and has a strong impact on the final output of the compiler.

Motivation

- An AST can be edited and enhanced with information such as properties and annotations for every element it contains. Such editing and annotation is impossible with the source code of a program, since it would imply changing it.

- Compared to the source code, an AST does not include inessential punctuation and delimiters (braces, semicolons, parentheses, etc.).

- An AST usually contains extra information about the program, due to the consecutive stages of analysis by the compiler. For example, it may store the position of each element in the source code, allowing the compiler to print useful error messages.

Resources

- Interpreter vs compiler: https://techdifferences.com/difference-between-compiler-and-interpreter.html

- What is object code?: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object_code

- Statically Typed vs Dynamically Typed Languages: https://www.baeldung.com/cs/statically-vs-dynamically-typed-languages

- What are Parsers?: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parsing

- LL Parser: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LL_parser

- LR Parser: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LR_parser

- Formal Grammar: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formal_grammar

- Context-free grammar: https://brilliant.org/wiki/context-free-grammars/

- Backus–Naur form: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backus–Naur_form

- What is syntactic ambiguity?: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syntactic_ambiguity

- What is an abstract syntax tree?: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abstract_syntax_tree